11 Nov Featured in an interview with Adrian Ioniţă from EgoPHobia

Translated (and transcribed) into French & Romanian

EgoPHobia [εγωφοβια] is an independent cultural e-journal published (initially) every two months dedicated mainly to original contributions in literature and philosophy.

Click here for the full interview.

It’s possibly the most comprehensive interview that I’ve done up to date. Big thanks to John Manyjohns for his contribuations to it (and for making sure that I didn’t come across like a complete moron).

We aim to be rather than to seem

[An interview with American Artist Sean Orlando]

by Adrian Ioniţă

cliquez pour la version française

click pentru versiunea română

As a living thing, the Steampunk Tree House (SPTH) creates an experience that is as varied and mysterious as the people who interact with it. It creates thoughtful nostalgia, it encourages play, to imagine another time, place and reality. It is an artistic representation of the human drive to re-create, industrial inventiveness and how we strive to mimic nature’s design while at the same time, destroying it. It is a place where fantasy intersects with reality. The steam calliope plays music, the potbelly woodstove is functional, and the clockwork vulture flaps its wings. We use real live steam produced by working steam engines to power the Tree and to provide steam effects for the branches and trunk. Even though its reality alludes to a very dream like state, nothing is false in its existence…

[Sean Orlando]

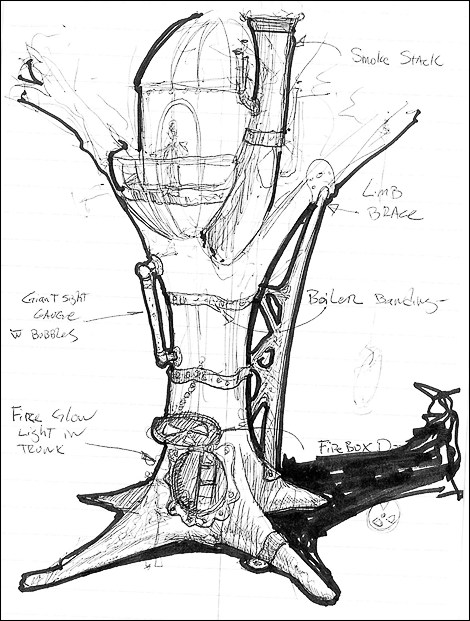

[The Stempunk Tree House © drawing by Shane Washburn]

Click on the picture to see a Quicktime movie

Adrian Ioniţă: Sean Orlando, you are L’enfant Terrible of a project that, since its inception in 2007, is burning in the imaginations of many artists and art lovers around the world. Tell me a bit about the piece and its creation.

Sean Orlando: First, I will give credit where it’s due, there were in fact many “creators†of the Tree House. I conceived the Tree House project, acted as Artistic Director and “drove the bus†as it were… but there were many contributors, artists, design engineers, structural engineers, barnyard engineers, scientists, computer programmers, software developers, carpenters, visionaries, fabricators, industrial designers, geeks, dorks, writers, and at least one wild-child. Many people contributed to the Tree House on so many different levels, which is why it is such a magical piece and why I think it affects people the way it does. What is truly special about it are the people who worked on it with me. Because of this project, a lot of amazing friendships and relationships were forged. The creative process is what motivates me the most… the act of making something and why… the manifestation of an idea or concept or message, to make a thought tangible… to share it with other people, allowing them to cooperatively create their own experience around it. It can be challenging to work with so many personalities on large projects.. An unexpected by-product that came out of this project was a sense of collaboration, artistic invention, and creative problem solving.

[Sean Orlando © photo by John Curley]

Adrian Ioniţă: Is there a connection between your life experience and the Tree House project?

Sean Orlando: I grew up in New York State, a geographical region that contains both Manhattan on one end and acre upon acre of countryside on the other. My parents had a plot of land and there were many trees on the property. They divorced when I was very young, which was very hard on me and on my younger sister, a time of transition, so I have very stained memories of my father from that time. I remember… he built a tree house and zip-line in the back yard. It was a typical kid’s tree house made of 2×4 lumber and plywood. At the time, it seemed tremendously spacious and elaborate in its design. It stretched between three trees and gave me a special “secret place†of my own that to a kid felt timeless, free of transition and conflict. I feel a strong connection with my father and have faint memories of many father/son projects that we worked on together when I was young. These are definitely a part of that bond and childhood memory. As an adult, I am a working Industrial Artist, Artistic Director, and Project Manager. I would like to think part of who I am and what I do commemorates the good in my relationship with my dad. Really, a tree house is a place to escape to, a safe haven where you go and…

Adrian Ioniţă: …and dream.

Sean Orlando: Yes, you go to dream, and you are inspired to get away from the nonsense of life, to refresh. When I was 18 and graduated from high school, I wanted to explore and see the world. I had never traveled very much even within my own country, so I went to France and backpacked around Western Europe for three months. When I returned, I worked for a while to save up money and then traveled cross-country on a motorcycle until I found the San Francisco Bay area. It is where America’s hopes and dreams run into the Pacific Ocean, sort of the furthest West the American spirit drives you if you still want to be around people and part of the world. I settled here and ended up at University of California at Berkeley, where I studied fine art, art history, performance, and site-specific installation. It was an incredible and challenging academic experience that I will always value.

I then discovered The Crucible, a non-profit industrial arts school and education center that serves both the local community and the broader arts and crafts community. I was hired to teach adults and children metal fabrication techniques and how to truly shape and define what they wanted to do artistically. We have a machine shop, full welding shop, foundry, smithy and a kinetics department… we work in glass, wood, ceramics and jewelry. It’s a great place that really helped to motivate and inspire me to work within a community of artists. It’s a non-competitive artistic environment where we encourage people to just create, learn, and have fun. We are also teaching local underprivileged kids how to weld, blacksmith, work on bicycles and explore their creativity in a positive way in a safe environment. On the other hand, there are so many resources here for artists of my type, who work with steam power.

[“Steaming Branchesâ€, the Fire Arts Festival in Oakland © 2008 photo by Joy Busse]

Adrian Ioniţă: Why steam power?

Sean Orlando: I think that there are a lot of people out there who are simply dissatisfied with throwaway bottle-fed art and consumption artifacts that have been forced upon us by sheer repetition and rote consumption. So, as an antidote, we look to a time when care, design and artistry were applied to the everyday life in a more lasting way. We are appealing to a different non-dominant ideology. Modern design can be very cold and rectangular, so hidden as to be aesthetically unreachable, smooth, a zipless totalitarianism. Our society has become wholly reliant on internal combustion and oil, to the point that we’ve depleted our natural resources and destroyed the environment. The social contract is not as it should be, between people and communities, but between large business concerns and the excesses of consumption. Steam power ruled the day for many, many years and played a big part in industry and the private sector. I am NOT saying that steam is the answer, it’s a metaphor. It’s a cautionary tale. It works nostalgically by reminding people of a supposedly “simpler†or “purer†time when invention, progress, and discovery were the driving force, a source of hope… not money, power and convenience. Of course, this nostalgia only works if people forget the Industrial Revolution and its terrible social and environmental discontents. The cleverness of art, like steam, is that it can do two things at once even if they’re opposed.

Adrian Ioniţă: Many are blaming consumerism for our alienation in the modern society.

Sean Orlando: I wouldn’t disagree. For instance, in the States, big chain stores are sprouting up everywhere; you can buy “everything you need at an affordable priceâ€â€¦ We don’t need to know how to make anything anymore or fix anything anymore… we can just go to the store and buy it… It’s an empty ecstasy of ideal forms, people trap themselves in a land of plenty, the ultimate consumption fantasy. Moreover, these bountiful goods are often made in a country with cheaper production costs under conditions that do not favor the workers, it is cheap and affordable in the short term. If it breaks, we just throw it out and replace it with another. We are losing the value in things because they are all mass-produced and not made to last. I’m afraid that with the current path that we’re on, we’re going to lose the ability to take care of ourselves. If I’m hungry, I don’t need to cook anymore, I can just throw a pre-made food-log into the microwave and 3 minutes later, I’ve got a full meal. Who grew the food? Who packaged it? Where does all my garbage go? Where does my water come from and where does it go? Where do all our clothes, toys, and household goods get made? Most people don’t care to know. We lose the value of things when the humanity of the people that made them is obscured. As consumers, to be estranged from our own productive power is to be alienated from our own creative power. In a relatively homogenous society, it’s not surprising that some people are looking for an alternative way of living their lives. Large, collaborative art projects can go a long way in re-connecting people with people; this is the promise of interactive art.

[KSW at the Edwardian Ball, San Francisco 2008 © photo by Heather Smith]

Adrian Ioniţă: I understand that all this passion for steam started with Kinetic Steam Works (KSW).

Sean Orlando: I helped establish Kinetic Steam Works in 2005. We started out with one enormous 9-ton (8,165 kg) steam engine and, with the exception of Zachary Rukstela and his experience on the Jeremiah O’Brien (one of only two currently operational WWII Liberty ships), none of us were familiar with the mechanics, operation, or function of steam engines! However, we figured it out. There is a lot of kinetic motion within a steam engine’s myriad of moving parts, all of which needed to be oiled and maintained. Water boils and builds up pressure, and under the right conditions, you can harness the power of pressurized steam to operate equipment, pumps, machinery, or in our case… kinetic art.

There is an organization in Northern California called Roots of Motive Power. They’re a non-profit group that does steam education and historic preservation of steam equipment used in California, from locomotives to 1880’s logging engines. We try and go up several times a year to volunteer and to take an annual steam operation and safety class with certification. It is a two-day class that we all attend to maintain our familiarity with steam power, best practices, and to also learn from the old timers who have worked with steam all their lives. Steam engines are functional and powerful, but within that functionality there is incorporated a beautiful aesthetic.

Adrian Ioniţă: In his controversial Design Observer article, “Steampunk’d, Or Humbug by Design,†Randy Nakamura’s critique of Steampunk quotes you and mentions KSW, suggesting that the Steampunk movement as a whole and your own fascination with steam power in particular is naive and uncritical. Please tell me something about the development of the Steampunk phenomenon.

Sean Orlando: It moves on different fronts. There are people who are creating artwork that is aesthetically beautiful, intentionally made with a particular look and feel, using Steampunk tropes like wood, brass and rivets, modding contemporary devices like computers, guitars or bicycles, and making them look “steampunk†or “old fashioned†in a way that appeals to techno-savvy hipsters. On the Steampunk continuum there are also a number of artists who are working with recycled/scavenged and reused materials, boilers, steam, kinetics, figuring out how things move, and building creative communities. Keep in mind that Steampunk exists as a social movement NOW rather than at some other time due to wider historically specific social forces. I think it’s a response to car culture, peak oil, environmental calamity, de-humanizing labor and production conditions in a global economy, and the hyper-proliferation of commodity forms.

I read Randy Nakamura’s article and thought “right on.†There hasn’t been enough critical interest in the movement. Without critical interest, the movement can’t grow. Critique furthers the discussion, motivates it. It keeps creativity honest even if the source of the critique is disingenuous. For those who haven’t checked out his article, if I may paraphrase his elitist critique: the steampunk movement is another petite-evil of some Culture Machine, a crass consumption pattern turning into a brand, a sort of unoriginal “bad†post-modern artifact that eats its young and forgets its historical referents, it’s false consciousness masquerading as liberating aesthetic practice, artists are dupes without agency, etc. In his own words, “Steampunk is humbug design, scrap-booking masquerading as the avant-garde.â€

Mr. Nakamura’s resume indicates that he’s a graphic designer by trade, with experience in branding and marketing. As a freelancer for Ogilvy & Mather’s Brand Integration Group, he credits himself with having worked on a brand identity campaign for a “laser skin treatment†company. It’s not difficult to throw stones in a glass house of mirrors, except that he neglects to hit himself too. Given his own position in the ideological apparatus of the culture industry, it’s not surprising that his critique comes off as hostile to a movement that questions mass production! In my work I connect people to people and people to art, he connects people to… laser hair removal.

Adrian Ioniţă: I invited him on EgoPHobia for an open talk, but I did not received yet a confirmation.

Sean Orlando: Here’s his publicly viewable resume: RANDY NAKAMURA.

His fox in the henhouse positioning aside, I found the critique to be one sided. I give both artists and “common†cultural forms more credit and more agency. The DIY (do it yourself) movement is broad, from solar power, to electric cars, to clothing, housing, transportation, and food… it can be very empowering and liberating to create things yourself and connect with other people doing the same thing. Eventually creative communities form that transcend what brought them together. In terms of steampunk, or good art for that matter, if you can imagine a different world, it can fuel positive social change.

Steampunk is still outsider art, not mainstream design, despite the mainstream coverage, it hasn’t really been co-opted yet. Last I checked, McDonald’s wasn’t trying to sell a “McMutton Chops with cheese†and Coca-Cola hadn’t started laser-etching gears into the top of their cans, Barack Obama isn’t (yet) wearing a stovepipe hat and brass goggles. The steampunk aesthetic lends itself to pre-existing industrial arts creative practices, including creative recycling, scavenging, and reuse. It takes detritus, mass produced throwaways and plays with it, sometimes parodying its origins.

Randy Nakamura cited me speaking about how interesting it is to be able to follow the path of steam from the fire to the boiler, through the pipes to the gears to the final kinetic moment, etc. His response, I’m paraphrasing again, was that anything could be fascinating on that level if you knew enough to understand the technology or underlying processes. And therein lies the rub, circuit boards (his example) are alien to most people. Like combustion engines or brands, they’re hidden inside technology that people feel disempowered by.

His best point is certainly that the steampunk movement can be woefully ignorant of history. This is something we’ve tried to combat in our own work. The Tree House’s back-story is that it exists in a dystopic eco-disaster future where there are no trees anymore and people have no living memory of trees. Instead they take the idea of a tree and construct it as best they can from scrap. While this could be seen as tragedy, it’s absolutely not intended that way! It was designed to be joyful, exuberant, connecting, interactive, thoughtful, regenerative… and if you experienced the piece directly, that’s probably what you felt. Neither is KSW ignorant of history, we understand the irony in promoting, say, a 1920 steam powered farm traction engine as a tool of connection. We do not hide the proverbial “blood on the plough†that steam powered farming methods wrought through displacing indigenous North American peoples from their land. We don’t cover up the railroad’s role in America’s westward expansion and “manifest destiny.†Nor are we unfamiliar with the Industrial Revolution and British Empire.

Being the consummate outsider artist, I’d say the people involved with KSW are more accurately identifiable as “Steamdorks†rather than “steampunksâ€â€¦ we’re just kind of dorky about it… we like old technology and how beautiful it is… we appreciate the engineering that went into designing these monstrous industrial instruments and are having a lot of fun devising and inventing new ways of harnessing and playing with them. We’re artists and mechanics. We own our own agency. There are some amazing “Steampunk Artists†out there, and I’m happy to see that this new genre has gotten the recent attention that it has… Wow, that was a long answer!

[The Steampunk Tree House at the Burning Man 2007 © photo by Zachary Wasserman]

Adrian Ioniţă: How was the Steampunk Tree House project started?

Sean Orlando: I have been going to The Burning Man desert arts festival for 5 years. At its best, Burning Man is a marvelous celebration of outsider art and culture, a place, a state of mind where you really can have unique experiences. It remains one of the best venues to experience original, interactive, participatory art.

Art that incorporates fire has been huge out there. We got together and joked that we should do fire one better. Serendipity came a’ knocking and we acquired our first steam engine in 2006 and we thought, “how cool would it be to be the first steam engine on the Playa?!†So, we started talking with the Burning Man people at their headquarters in San Francisco about what we would need to do to make this happen. They were extremely supportive and the first steam engine landed in Black Rock City in 2006.

I have a number of friends who had proposed and made pieces for Burning Man in the past, Michael Christian, Orion Fredericks, Greg Jones, to name a few. I’ve also worked on many other people’s projects over the years. I saw what they had done and what hard work it was, but also how satisfying it was. So I had this idea of my own for a tree house, inspired in part by Burning Man’s 2007 Green Man theme. I started to sketch out and draw what I thought it would look like. I put together a funding proposal with my friend John Manyjohns (also a founder of KSW) and we submitted it to The Burning Man staff and grant selection committee, they approved it, and we ended up getting funding to make it happen.

Adrian Ioniţă: I imagine the excitement after you found out that the proposal was approved! Please tell me something about the philosophical idea that connects the SPTH to the Green Man theme.

Sean Orlando: I was inspired to create the Tree House as a reaction against the things that I find most distasteful in this world and by the things that make this society and reality… ugly. I’ve touched on a lot of this over the course of the interview. In America, tree houses are very iconographic, they are a place to hide-away, they allow space for a different perspective on the world, and they remind us of a more innocent and simpler time. They’re considered to be regenerative. The Green Man is a reoccurring representation of a benevolent forest deity found throughout European history and pre-history. This entity is often depicted as a smiling, leafy, green anthropomorphic face. This is the deity that connects you to that which feeds you, cares for you, loves you, and looks out for you on a planetary level. While the SPTH wasn’t quite intended as a temple for the Green Man, it was intended to inculcate those feelings in participants, and it was obviously intended as a statement on how people find connection and humanity in the face of destruction and adversity.

On the other hand, we were confronted with more pragmatic issues, like structural engineering! We are talking about a Tree House that weighed 25,000 lbs (11,340 kg) and was over 40’ (12+ meters) tall, so safety was one of our biggest concerns. When you build a tree, people really want to climb it, like it’s in their blood. I worked with Corbett Griffith at Instinct Engineering to come up with engineered drawings of the structural elements, and with the help of other friends who are design engineers, mechanical and structural engineers, we figured out what we needed to do to pull this off…

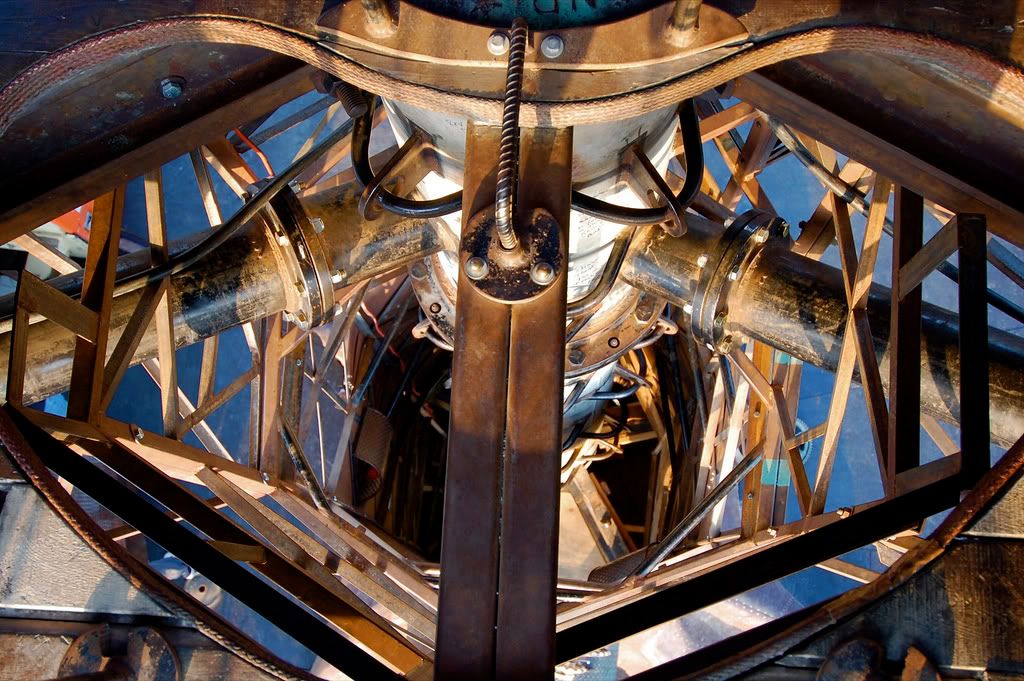

[Detail inside the SPTH© 2008 photo by Joy Busse]

Adrian Ioniţă: Talking about climbing, please describe the ins and outs of your project.

Sean Orlando: You enter through a door in the trunk and climb up rungs, up through the floor and into the house itself. The Steampunk Tree House is not only a structure, object or thing. With the incorporation of live steam effects, the SPTH became a changeable, living work of art that came alive through your experience of it.

The whole tree was hooked up to a steam engine and it incorporated a maze-work of steam pipes and valves that were designed to open and close various junctions on the tree. Each of the branches had steam lines running through them, so that when a valve is opened, it would send steam through the branches and into the atmosphere. On another manifold, a custom steam calliope (designed & fabricated by Nathaniel Taylor, one of the artists working on the project) had an interface to release steam into nine whistles installed on the branches, so that you could be inside the house pushing these levers, which opened the valves to release steam into the whistles, and play music. On the roof we installed a larger whistle (loaned to us from my friend Bob Hofmann) about 36 inches tall with a 6-inch bell (it formerly signaled shift changes in a factory), which made variable guttural resonance sounds. It really engaged people to play music using steam. On one of the branches, we had a vulture made by another member of the crew, Max Chen. Its geared wings flapped by pulling on a lever on one of the balconies. We had many innovations fulfilled in this project and all were done within a particular aesthetic. As Artistic Director, it was challenging to get this many people, not necessarily to conform to it, but to appreciate and understand how to blend all the parts together harmoniously.

[Steampunk Tree House transportation © photo by Alan Rorie]

Adrian Ioniţă: How did you do the transportation, assembly and disassembly of the piece?

Sean Orlando: Traditional sculptures, or works of art of this type, usually go into a permanent installation, but we had to figure out, along with designing it structurally and aesthetically, how would it come apart in pieces such that it could be re-assembled very easily, efficiently, and safely. Then, there is the transportation. It is heavy, requiring two 18-wheeler semi-trucks to move, 10-ton cranes to assemble, forklifts, many logistics… We’ve installed it three times so far.

We built it in two different locations because it is so big, none of the West Oakland arts’ production warehouses that we have access to, were big enough to accommodate the entire structure as we were building it. The house and the trunk and the roots were built in one warehouse with me and my crew (the now defunct NIMBY), while the branches and the upper section of the trunk were built in another warehouse with Steve Valdez and his crew. Steve is an amazing fabricator and designer and we wouldn’t have branches on our Tree without his dedication to the project. We never actually had it fully assembled until we got up to Burning Man. Even with an excellent crew and great planning there were a few nervous moments. I thought about our main sponsor, our donors… all the time, effort and goodwill of so many people were on the line… I will tell you, we were VERY happy when the moment of truth came and we matched the pieces together and everything fit as it should.

Adrian Ioniţă: Did you use paint to achieve the overall look of the sculpture?

Sean Orlando: The trunk and exterior walls have this amazing, rusty patina. When we started, we used brand new sheet metal and everything looked bright, shiny, and silver, almost like stainless steel, kind of a Terminator look. We used a cold patina technique, and treated these surfaces to make it look like they’d been corroded under the elements for a very long time. The Tree’s back-story was that is existed 1,000 years hence, after the petrol-economy had collapsed. In the desert setting, it really did look like it had been there for a millennium. The fact that the branches are without bark, skin, or foliage adds to this feeling of weathering and decay. However, what the steam does is to create a kind of “living†foliage around the branches. A very interesting effect achieved with colored lights powered by solar panels and white milky steam, filtered with red and blue and green lights. Very dramatic. During the day, the tree was stark and naked, dusty, and during the night, with the steam engine providing steam for the branches, the whole tree blossomed with moist imagery, hallucinogenic foliage that you might see only in some alternative realities or a dream.

[SPTH at Burning Man © 2008 photo by Fred von Lohmann]

Adrian Ioniţă: The atmosphere around the Steam Punk Tree House is just Mind blowing. It is like an object descended from a dreamscape.

Sean Orlando: Caro & Jeunet’s The City of Lost Children is one of my favorite movies, and was a significant inspiration. One thing that sticks with us and with me, is a phrase that I use repeatedly: “We aim to be rather than to seem.†Even though we were creating this atmosphere in this environment, nothing is false, it’s all a reality alluding to a very dream like state. We have the reality of all the moving parts and the steam engine, the kinetic elements of the tree and nothing was built falsely. Of course it’s not “real,†the tree isn’t 1,000 years old, but neither did we want it to be an endless L.A. like surface without substance. Substance lies in the manner of consumption. I have a strong distaste for many architectural elements or building techniques that you see out in the world today, which are built falsely. Things like drop ceilings, faux wood paneling, florescent lighting, cubicles, strip malls, prefab and mass produced architectural elements, plastic, blinky lights, Styrofoam, and so on. Things that are constructed to look like something but are nothing more than a sham.

The Tree House is all steel, angle iron and flat bar. The main trunk is a 2-foot diameter structural pipe, the main three branches that hold the house up are all made of 8-inch diameter structural pipe that is ten feet long. We tried to build everything to be real and solid, as opposed to hollow and false, and I think that this feeling really came across. At The Burning Man opening ceremony, we had about 45 people up there; Arm in arm with each other, all the people that worked at the project. Normally, the house can accommodate 20 people and the trunk about 10. When we installed the house in Southern California at the Coachella & Stagecoach Music Festivals, we had 20 people in there at one time, and that was comfortable.

Adrian Ioniţă: What was the reaction of the art world after The Burning Man?

Sean Orlando: I had a lot of people approach me about the sculpture, interested in what I was planning on doing with it and how much it would cost to install the piece. I was in negotiations to possibly install it at the Google headquarters, and also had a good reaction from people involved in galleries and museums, but the biggest concern, given the fact that the piece is interactive and has a large dimension and weight, is liability, especially in litigious America. Right now it is in storage and we are working very hard to find a good home for it.

[The Lumbering Contraption © photo by Alan Rorie]

Adrian Ioniţă: What are the most recent and/or future projects that you are working on?

Sean Orlando: The project I am working right now is a human powered vehicle, a gigantic hamster wheel that’s run on train tracks, powered by people inside the wheel. We call it the Lumbering Contraption. It was conceived for The Great West End and Railroad Square Handcar Regatta, held on September 28th, 2008. A very simple mechanism, designed with a pilot section that is very ornate. It has a certain function and ornaments that are also very beautiful. It’s going to get a cowcatcher in the front, not that it needs it, but that is a part of the humor and combinations of beauty within function. The majority of the crew working on it also worked on the Tree House.

Kinetic Steam Works has spent the past spring and summer restoring a 40′ long steam powered Scripps style stern paddlewheel boat. The Wilhelmina is powered by a water tube boiler and two steam engines. The fuel that we use to fire the boiler is atomized bio-diesel. We use atomized fuel to create a fire in the firebox, which heats up water in the boiler tubes, which creates steam under pressure. The steam is controlled by a series of valves and pipes that run all throughout the ship. This complicated series of valves, pumps, and plumbing allows us to easily release steam to the port and starboard steam engines. The engines are in sync with each other and are both eccentrically connected to the paddle wheel at the stern of the boat. The power that we create from our onboard steam system is what propels the boat forward… quietly and gracefully. The boat is currently in NYC, having gone down the Hudson River on a 3-week trip in August 2008.

[Floating sculptures © 2008 Nathaniel Brooks]

Click on the picture to see a slideshow done by The New York Times

Adrian Ioniţă: Why New York?

Sean Orlando: KSW has hooked up with a New York based artist by the name of Swoon, as well as many other artists from New York to San Francisco. We were part of a floating artistic armada that went down the Hudson River from Troy to Long Island City (NY) along with 7 other custom engineered and constructed boats and rafts, all powered by alternative energy propulsion systems. The project was called, “The Swimming Cities of Switchback Sea.â€

The boat was donated to KSW and was in serious disrepair when we got it. The crew worked tirelessly to restore it in time to take it overland from Oakland, California to Troy, New York. Sections of the steel hull were taken out and replaced by us. The boiler was removed and repaired and modified to spray bio-diesel All the plumbing is new and re-designed by Stephen Rademaker, Andrew O’Keefe and Greg Jones. The paddle and engines were rebuilt. It’s a completely new boat. I had the unique experience of being a passenger of the fleet from Kingston to Verplunck, NY, it was a lot of hard work, but it was an experience that I will always treasure. I fired the boiler, stood at the helm, greased the engines, set anchors, and tied off spring-lines. We camped on the river, sleeping on the boat and camping on islands. We explored an island with an abandoned castle on it… It’s the closest a Yanqui can get to the Mark Twain idyll.

Adrian Ioniţă: Have you ever been to Eastern Europe?

Sean Orlando: I’ve never traveled in that area, but I’d like to. I’d like to learn more about Romanian culture and see what’s going on in that part of the world; It seems like a very interesting place to visit. Some of the artifacts we talked about before this interview, like the beautiful iron tree from the city of Timisoara, or traditional folk art forms or castles from Transylvania are really fascinating. It would be great to meet Romanian artists and work on some artistic projects with them.

Adrian Ioniţă: EgoPHobia is building that bridge in this very moment. Sean Orlando, thank you for sharing your thoughts with our readers. Special Thanks to John Manyjohns for his help with this interview and to Drea Roemer for her love & support.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.